Table of Contents

Introduction to the Skull (Cranium)

Skull Anatomy: Neurocranium vs Facial Skeleton

The Cranial Cavity: What It Is & How Big It Gets

Protective Functions of the Cranial Cavity

Skull Development: Sutures, Fontanelles & Ossification

Clinical Considerations: Injuries, Infections & Pressure

Comparative & Evolutionary Insights

Bonus: Sinuses, Foramina & Cool Skull Facts

1. Introduction to the Skull (Cranium)

The skull, or cranium, is not just a rigid shell—it’s a complex structure made for protection, support, and function. Derived from Latin and Greek roots, “cranium” simply means “skull,” while the English “skull” has Germanic origins. Together, they give us a solid term to describe the bony case that houses our brain.

For a foundational breakdown of skull bone types, structure, and diagrams, check out Discover Wonders of Cranial Bones.

2. Skull Anatomy: Neurocranium vs Facial Skeleton

Your skull is composed of two main parts:

Neurocranium (braincase): Contains 8 bones forming a robust casing.

Facial skeleton (viscerocranium): Encompasses 14 bones responsible for facial structure, chewing, and housing the ear ossicles.

Bones of the neurocranium (8): frontal, two parietals, two temporals, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid.

Bones of the facial skeleton (14): maxillae, zygomatic, nasal, lacrimal, palatine, inferior nasal conchae, vomer, and mandible, plus the 3 tiny ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes).

3. The Cranial Cavity: What It Is & How Big It Gets

3.1 What is the Cranial Cavity?

The cranial cavity—known in Latin as cavitas cranii—is the internal space made by the 8 neurocranium bones that houses the brain. It also contains the protective meninges and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

3.2 Average Cranial Capacity in Adults

In adult humans, cranial capacity typically ranges from 1,200 to 1,700 cm³, with average values around 1,400–1,500 cm³.

3.3 Why Volume Matters

The cranial cavity isn’t just a brain container. It’s a carefully engineered space that allows fluid flow, pressure equalization, and nerve protection. Any variation—such as swelling, bleeding, or compression—can result in serious complications.

4. Protective Functions of the Cranial Cavity

4.1 Brain Protection & Meninges

The brain is secured by three layers of meninges and bathed in cerebrospinal fluid, which cushions against shocks. These reduce trauma during impacts, while fractures can lead to dangerous bleeding or infection.

4.2 Cranial Nerves

Twelve pairs of cranial nerves pass through foramina in the neurocranium, controlling critical functions like smell, sight, chewing, swallowing, and facial movement.

4.3 Pituitary Gland Housing

The sella turcica, a saddle-like depression in the sphenoid bone, protects the pituitary gland, a hormone powerhouse regulating growth, stress response, and reproduction.

5. Skull Development: Sutures, Fontanelles & Ossification

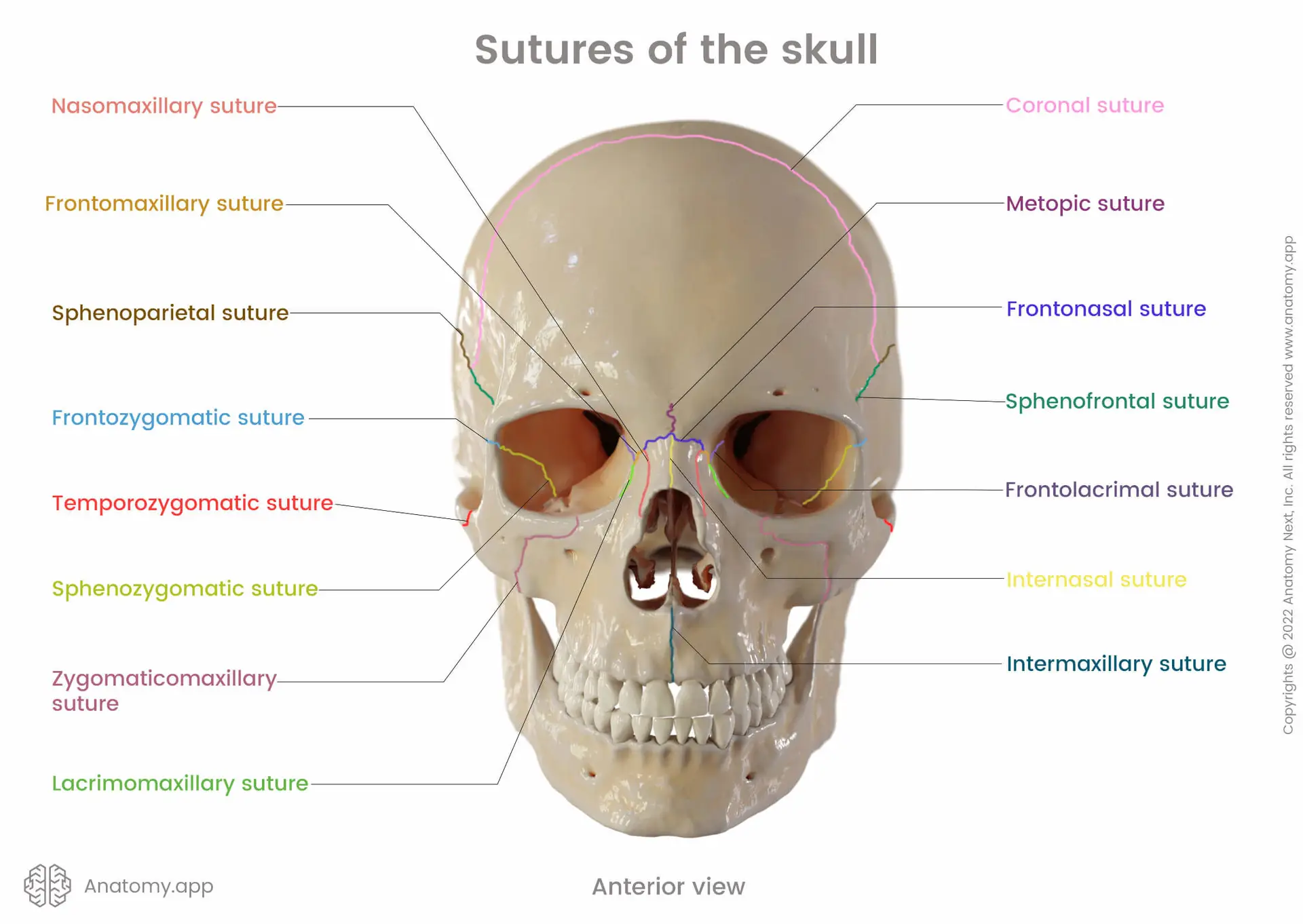

5.1 Sutures & Fontanelles

Cranial sutures (coronal, sagittal, lambdoid, and squamous) are fibrous joints connecting skull bones. These remain open during infancy to allow brain growth and skull molding.

Fontanelles (soft spots):

Anterior: closes between 9 and 18 months.

Posterior: usually closes by 2–3 months.

Others (sphenoidal, mastoid): close by 6–18 months.

5.2 Ossification Patterns

Most cranial bones form via intramembranous ossification, where bone develops directly from tissue. Some skull base bones use endochondral ossification, forming from cartilage.

Opportunity for detailed visuals: Fontanelle closure timelines and ossification charts help convey this to readers—ideal for parents and med students.

6. Clinical Considerations: Injuries, Infections & Pressure

6.1 Traumatic Brain Injuries & Concussions

Impacts may cause linear or depressed skull fractures. The thin area called the pterion is a high-risk zone—damage can rupture arteries and lead to epidural hematoma.

6.2 Meningitis & Intracranial Pressure

Meningitis is an infection of the meninges that demands urgent care. Fontanelle bulging in infants can be an early warning sign.

6.3 Craniosynostosis

This condition causes early fusion of cranial sutures, altering skull shape and potentially compressing the brain. Treatment typically involves corrective surgery.

7. Comparative & Evolutionary Insights

7.1 Skull Evolution in Hominids

Homo sapiens: 1,400–1,500 cm³

Neanderthals: up to 1,740 cm³

Homo erectus: ~900–1,100 cm³

Australopithecus: ~438 cm³

These changes reflect adaptations for cognitive function, speech, and locomotion.

7.2 Axial Skeleton Context

The skull caps the axial skeleton, linking with the vertebrae at the foramen magnum. Its placement helps balance the head over the spine—crucial for bipedal motion.

8. Bonus: Sinuses, Foramina & Cool Facts

Paranasal sinuses help lighten the skull and affect voice resonance.

The foramen magnum allows passage of the spinal cord; its location affects posture.

Trepanation, or ancient skull drilling, was practiced for both surgery and rituals.

Some fossil skulls (e.g., Boskop Man) had unusually large capacities—up to 2,000 cm³.

FAQs

What’s the average adult cranial capacity?

Around 1,400 cm³, varying by sex, ancestry, and age.Why are fontanelles important?

They allow head flexibility during birth and provide room for rapid brain growth postnatally.What’s the clinical concern with fontanelle bulging?

It can signal increased intracranial pressure or meningitis—requires urgent attention.

Leave a Reply